Can you imagine a boy who wants to attend high school at 11 years old being told that he has to wait until he is 13? Can you imagine that boy being told he is not allowed to have books for two years? Imagine that 11-year-old boy saying, “If you do that, you might as well kill me now, cause I’ve got to have my books!”

This was Elihu Thomson, future great American inventor and prominent resident of Swampscott. He used those two years free of formal schooling to study “The Magician’s Own” book, which contained tricks and puzzles, but also experiments in electricity and chemistry.

“The electrical chapter was what struck me at once,” recalled Thomson.

The book explained how to make an electrical machine out of a wine bottle. Young Thomson made the machine and was able to get his first electrical sparks out of it.

“My father rather poo-pooed the magnitude of my efforts and I thought I had to get even with him somehow,” said Thomson in a 1932 interview with Edwin W. Rice Jr., his student, assistant, and ultimately the president of the General Electric (GE) Company.

Thomson made a bigger battery for his wine-bottle device, which shocked his father when Elihu prompted him to touch it.

Thomson was born on March 29, 1853, in Manchester, England. He was the second-eldest child of a Scottish father, Daniel, and an English mother, Mary Rhodes, who had 11 children, six boys and five girls. Four of the children died in their early youth.

In 1858, his parents decided to emigrate to America due to scarcity of work. They settled in Philadelphia, the second-largest industrial center in the U.S. at the time. Thomson’s father was a skillful mechanic, who traveled to Cuba and other places to set up sugar-refining machinery. However, he struggled to support such a large family. When Thomson finished high school, the family could not afford to send him to college.

Thomson showed curiosity and extraordinary abilities for a child from a young age. His mother discovered that he knew the alphabet and could recite it both forwards and backwards at 5 years old. Young Thomson taught himself.

He was highly influenced by his father’s work as an engineer and machinist as well. By his own account, he was able to visit various industrial establishments and witness the industrial processes going on, both in chemical work and also in mechanical constructions. He actively studied the two volumes of the “Imperial Journal of Arts, Sciences and Engineering,” which his family had at home.

“I was always interested in what was going on around me, such as the laying of water pipes and gas pipes in the streets, the building of sewers, etc., and spending hours watching the operations,” said Thomson.

When he was 10 or 11 years old, he constructed a small model of cupola furnaces with fan blowers and succeeded in melting cast iron; however, the iron that was melted was not sufficient enough to run into a mold, which was Thomson’s ultimate goal.

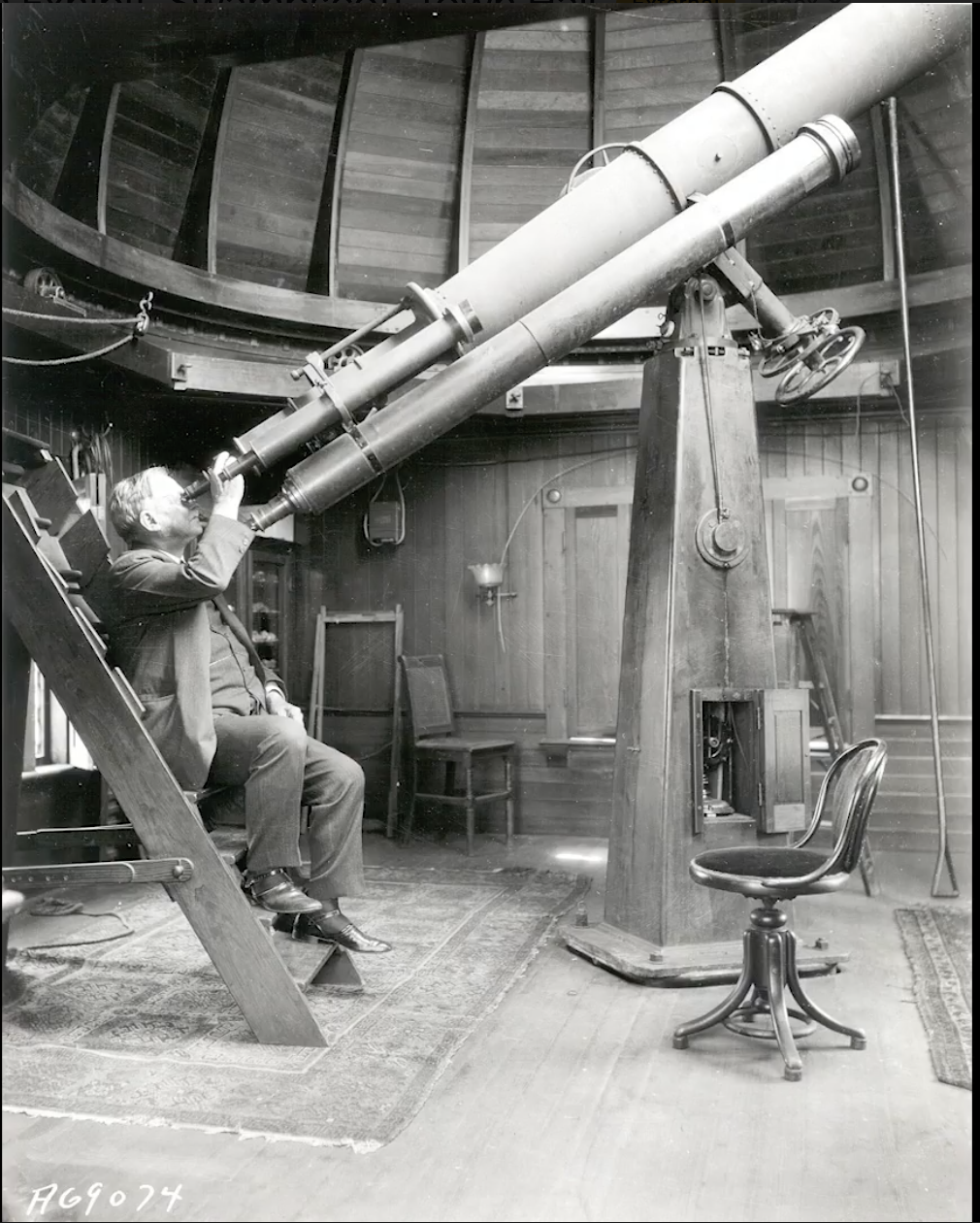

He also had a great interest in astronomy. In the summer of 1858, when he was 5 years old, Thomson saw the Donati’s comet, and in 1867 he witnessed spectacular meteor showers. In 1878, he published an account of a method of grinding and polishing glass specula, and in 1899 he began the construction of a telescope for his private observatory, including making the optical parts for the 10-inch reflector. The observatory was located on the lawn near his house, which is now the Swampscott Town Hall, but was later removed and donated to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia.

Thomson attended the boys’ Central High School in Philadelphia. He graduated with honors and accepted employment in a commercial laboratory which analyzed iron ore and other minerals. After about six months he returned to Central High School with a title of adjunct professor to the Department of Chemistry and a salary of $500 per year (about $10,730 in today’s money).

Student Edwin Rice was 14 when he met 23-year-old professor Thomson at Central High School, who was keen to teach the eager student.

“To me he has been ‘my professor’ ever since I first met him,” Rice said. “It is my recollection that there was no question that I asked to which I failed to obtain a satisfactory reply, expressed in language that I could understand.”

One of the senior professors whom Thomson assisted at Central High School was Edwin J. Houston, who held the chair of Physical Geography and Natural Philosophy. The two soon started to collaborate in the evenings on investigations and formed a long partnership, inventing devices, especially in electricity.

“Not infrequently I would leave home after breakfast and not eat or drink anything until I got home again at 11 in the evening,” wrote Thomson. “I’ve always believed in long hours. It’s the only way to get things done.”

In 1876-77, Thomson gave lectures on electricity at the Franklin Institute, an important center of American science and technology in the 19th century. The following year, he and Houston tested dynamos of different types at the institute, which prompted Thomson to design and build a dynamo for a single-arc light.

That formed the basis of the later development of the Thomson-Houston arc-light system that involved several unique features, including three-phase winding and the automatic regulating system, which kept the current in the light circuit at an even value, no matter how many lights were on that circuit.

Next, they invented an air-blast method to extinguish an arc, the magnetic blowout which employs a magnetic field to extinguish an arc and a lightning arrester.

Thomson and Houston were able to get business backers to market their lighting system. They have created a lighting system for a bakery that was open all night long and for a brewery.

In 1880, Thomson was approached by Frederick Churchill, a young lawyer from New Britain, Conn., who had just organized the American Electric Company. The American Electric Company bought control over the Thomson-Houston patents and Thomson resigned from Central High School to become an “electrician” at the company.

When leaving Philadelphia for Connecticut, Thomson took Rice with him. In New Britain, Thomson focused on improving the arc-lighting system but since the market for commercial electric-lighting systems didn’t exist yet, the company was struggling.

Meanwhile, in Lynn, a group of investors, including Silas Barton, Henry Pevear, and shoe-manufacturer Charles Coffin, were looking to invest. Electrical lighting looked like a promising new industry for them.

In 1882, Barton and Pevear went to Boston to examine an electric-lighting system that had been installed in a shop on Tremont Street. They slipped down the back stairs to the dynamo that was powering the system and located a brass plate that read “American Electric, New Britain, Connecticut.”

The next day, they traveled to New Britain, where they met Thomson and his associates. They convinced Thomson to let them buy the American Electric Company, leave New Britain and form a new company with them in Lynn.

Coffin became the president of the new company. With Coffin assuming the burden of finance and management, Thomson was free to give undivided attention to research and technical development, and for the first time he was able to surround himself with competent assistants.

The Thomson-Houston Electric Company installed street lighting at 166 Market St. in Lynn, and the merchants in the area began to subscribe to their service. Market Street became the first street with commercial lighting in New England.

The Thomson-Houston Company grew rapidly. In 1884, it employed 184 workers. By 1892, when it merged with its competitor, the Edison GE Company of Schenectady, N.Y., the number had grown to 4,000 employees. The result of the merger was the GE Company, with Coffin as president and Rice, who had been manager of the Lynn plant, as vice president and technical director.

Thomson’s contributions to the success of this great industrial organization was in industrial research.

Thomson married his first wife, Miss Mary Louise Peck, in 1884. Together they had four sons — Stuart, Roland, Malcolm and Donald. They lived in Lynn until 1889, when Thomson purchased a prime piece of land overlooking the Atlantic Ocean from the Swampscott Land Trust.

The Thomson house was designed by architect James T. Kelly in the Georgia revival style and was built in 1889. Thomson designed and built a steam boiler to heat the house, installed his electric-lighting system, but also included eight fireplaces in the house.

The second floor of the carriage house was designed and built to accommodate a laboratory for his work.

He also installed a pipe organ — the one that he built as a teenager, which he had brought to Swampscott from Philadelphia.The pipes were installed in a grid above the second-floor ceiling.

He also built a miniature railroad of about 100 yards for his sons.

He donated the land next to his home to the Town of Swampscott for a town library to be built.

One might think that a scientist of his intellect and intense work ethics would be reserved and strict. But Thomson lived a rich family life, actively engaged with his sons, and went camping and hiking in the Adirondacks and Catskills.

There is old video footage showing him playing with his grandchildren in the large front yard of his Swampscott home and reading to them.

The Thomson’s house was always open to visitors, including other outstanding scientists of the time, including Nikola Tesla.

Thomson’s friend and MIT president from 1909-20, Dr. Richard C. Maclaurin, said that Thomson showed an intense desire to help all who were struggling earnestly with scientific problems. Many engineers came to him with their secret projects.

“They have done this, knowing that they had only to ask in order to get the full benefit of his imagination and his power, and that they need have no misgivings that he would take any advantage of their confidence or any credit for their work, for he has no touch of selfishness,” Maclaurin said.

Thomson was asked to become the MIT president as well, but declined the offer because he felt that the research he wanted to do would be hindered by the administrative work the position would require. Still, in 1920-23, he was convinced to assume the obligations of the acting president because the president of MIT at the time became ill.

After 32 years of a happy marriage, Thomson’s wife died in 1916. In 1923, at 70 years old, Thomson married again to Clarissa Hovey of Boston. Together they began to travel a lot.

The prominence of Thomson is indisputable. He took a prominent place among the brilliant group of scientists who worked on solving the problem of generating adequate current, including Brush, Edison, Siemens, Stanley, Tesla, Van Depoele, Weston, and others.

Over his inventor’s career, Thomson patented almost 700 inventions. He is still one of the leading patent holders in America.

His awards include the Franklin Medal, the Faraday Medal, the Hughes Medal of the Royal Society, the Edison Medal from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), the Rumford Medal, and the 1889 Great Prize from the Paris Exposition.

Thomson died at 84 on March 13, 1937. His home was partially donated to the town by his heirs in 1944.An ongoing exhibition of the artifacts of the inventor’s career and life, “Elihu Thomson’s Inventive Life,” can be viewed until April at the Swampscott’s Town Hall during normal business hours.