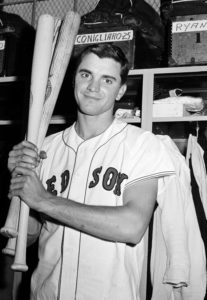

Boston Red Sox outfielder Tony Conigliaro is carried off the field on a stretcher by teammates and the trainers of both the Red Sox and the California Angels after he was beaned by Angels pitcher Jack Hamilton in the fourth inning of their game at Fenway Park in Boston, Mass., Aug. 18, 1967. (AP Photo/Bill Chaplis)

By STEVE KRAUSE

He had been in a slump. Tony Conigliaro, the 22-year-old kid who, earlier in 1967, had become the youngest player in the history of the American League to reach the 100-homer mark, was in a rut and hadn’t hit one out in 10 days.

“He’d had some pretty good stats up to that time,” said teammate and friend Rico Petrocelli, “but yeah, he was struggling. We always talked about waiting on the ball. When you’re in a slump you always tend to rush things. He wanted to wait on the ball. That’s what all the great hitters could do. Tony probably had that on his mind. Wait … wait … wait until the last second.”

“Unfortunately,” said Petrocelli, “it worked against him. He didn’t have enough time to get out of the way.”

Tony Conigliaro was a local idol — the Swampscott kid (via East Boston) and St. Mary’s graduate who had made his Major League debut with the Red Sox at age 19 and homered in his first at-bat, on the first pitch he saw off Joel Horlen of the Chicago White Sox in 1964, at Fenway Park.

In no time, he became the toast of the town. He even recorded rock ’n’ roll records.

“I remember seeing him open his trunk up once and there were all these 45s of ‘Little Red Scooter’ (one of his recordings that got local airplay),” said Frank Carey, a lifelong friend and teammate at St. Mary’s. “He loved that stuff.”

Just about every Red Sox fan probably wanted to be Tony Conigliaro, and a good many female fans surely would have dated him if they’d had the chance.

That all changed in a split second 50 years ago, on Aug. 18, 1967.

That hot August night was Tony Conigliaro’s Day of Infamy.

The Red Sox were playing the California Angels (as they were called at the time) and both teams were in the thick of a pennant race that — even that late into the summer — involved half of the American League’s 10 franchises (Boston, California, Minnesota Twins, Chicago White Sox and Detroit Tigers).

It began just like any other day.

“He took me into the park with him,” said Richie Conigliaro, the youngest of the three boys, who was 15 at the time. “I was his little brother. I liked hanging around with him, hanging around in the locker room. When it was time for him to go onto the field, I went into the stands.”

The game was scoreless going into the bottom of the fourth inning. Conigliaro, who had been dropped to sixth in the batting order by manager Dick Williams, had already hit a single to center field, and it looked like his newfound selectiveness, coupled with a renewed effort to get as close to the plate as he could, had paid off.

“He was a streak hitter,” said middle brother Billy Conigliaro, himself a player in the Red Sox minor league system at the time. However, he was home after doing a two-week stint in the Army Reserve and was planning to go to the game with his parents (Salvatore and Theresa), Richie and uncle Vinnie Martelli that night.

“We were talking at home that afternoon and he said he was going to stand closer to the plate and stay in a little longer before making a commitment to the pitch,” Billy said.

“(Tony) always crowded the plate,” said Carey, a member of the National High School Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame who spent 49 years at North Reading High. “He was fearless. I can remember back in 1964 he was going to face (Yankee Hall of Famer) Whitey Ford. “Now, Ford was well past his prime,” said Carey, “ but he was still, you know, Whitey Ford. But Tony says ‘I’m going to get him,’ and he did. He could always back it up.”

That confidence wasn’t anything new.

“One day in high school, we’re going up to St. John’s Prep and Danny Murphy (of Beverly, who later pitched for the White Sox and Chicago Cubs) was on the mound,” said Lynn School Committee Secretary Tom Iarrobino, a teammate of both Carey and Conigliaro in high school. “Same thing. ‘I’ll take him deep!’ We tell him, ‘Tony you can’t say things like that.’ Sure enough, he gets up and hits one out. He was only a sophomore at the time.”

To that point in the 1967 season, Conigliaro had hit 20 home runs and knocked in 67 runs, and was establishing himself as one of the premier clutch hitters in baseball. And with Carl Yastrzemski hitting in front of him for most of the season, they formed a potent 1-2 punch.

Conigliaro was the third hitter up in the bottom of the fourth.

George Scott led off with a single, and Reggie Smith had flied out.

“After that,” Richie Conigliaro recalled, “some idiot out in left field threw a smoke bomb onto the field, and that delayed the game for almost 15 minutes.”

Finally, Conigliaro dug in against Angels pitcher Jack Hamilton in his customary wide-open stance, legs spread apart, bat high behind his shoulder.

The ball came in, high and tight, exactly the type of ball a pitcher would throw if he wanted to back a hitter away — something much more common, and much better accepted, in 1967 than it is today.

“It was a fastball,” confirmed Petrocelli, who was on deck. “A lot of times, when you’re in a slump, you wait up there in case it’s a curveball or a changeup. Who knows? He may have been thinking about a breaking ball.”

Also, said Petrocelli, “Tony had a little blind spot inside. He got it a few other times too, in the back, or in the arm. I think he fractured his arm once.

“If he got a strike on the black (of either corner of the plate), you couldn’t throw it by him. He’d nail it. But maybe two or three inches inside, it’s like he didn’t move. It’s almost as if he lost the ball.

“Even though it was eye-high, it could be that he didn’t see the ball.”

Some other factors came into play, too. It was a warm night, and the center field triangle had not been cordoned off the way it is now.

“There were a lot of white shirts out there, in the line of his vision,” said Petrocelli.

Whatever the reason, Conigliaro never moved. The ball hit him flush on the side of his face, and, as it turned out, below the helmet line (few players had ear flaps on their helmets in 1967; after that helmets were designed with them).

Conigliaro fell to the ground immediately, face down.

“Everything,” said Petrocelli, “went silent. Everyone in the ballpark — and it was probably a full house — groaned and then went still.”

“I saw the whole thing,” said Billy Conigliaro. “It was terrible. We all thought it hit the side of his helmet and that he wasn’t going

to have permanent problems.”

However, one portent of how bad it was came when the ball did not ricochet, as it would have had it hit a hard, plastic object

such as a helmet.

“It went straight down,” Billy Conigliaro said. “I don’t even remember hearing any sound. And it went completely silent in

the stands. Everybody was silent.”

Despite all this, Billy Conigliaro and his family tried to remain optimistic.

“We thought he’d get up,” he said. “We didn’t find out until much later how bad it was.”

However, Richie Conigliaro said, “you knew it was bad when, after a couple of minutes, he still didn’t get up, and wasn’t even moving.”

Petrocelli knew immediately. “He was lying on the ground, face down, and holding his eye,” Petrocelli said. “I saw the side of his face start to blow up like a balloon, just like you were blowing up a balloon.

“It was so scary,” Petrocelli said. “I don’t know if it hit him in the eye directly, but certainly right below the eye. That’s why it blew up the way it did.”

Almost immediately, trainer Buddy LeRoux rushed onto the field along with team doctor Thomas Tierney.

“Right away, they called for a stretcher,” Petrocelli said. “They knew he was hurt real bad. I helped put him on the stretcher. I kept telling him, ‘Tony, you’re going to be all right.’”

By this time, the family had made it onto the field and saw him being placed onto the stretcher and whisked away to Sancta

Maria Hospital in Cambridge.

“We thought he was going to die,” Richie Conigliaro recalled.

“My poor parents. I mean, he was only 22. This was the ‘Impossible Dream’ year, and here we were.”

By the next day, after he’d stabilized, the question wasn’t whether he’d live, but whether he’d ever play again.

“You saw that picture of him, lying in the hospital bed, with his eye blackened the way it was, and you thought, ‘no way was he ever going to be able to play again,’” said Petrocelli, who, despite seeing his best friend on the team leveled by a fastball to the face, tripled immediately after the beaning to score both Scott and pinch-runner Jose Tartabull. The Red Sox won the game, 3-1, and, of course, went on to win their first pennant since 1946,

overcoming 100-1 odds.

Conigliaro, who was officially diagnosed with a detached retina, was done for the ’67 season. He was, however, with the team on the day it clinched the pennant.

The road back would be almost impossible, said Richie Conigliaro, but his brother didn’t give up easily.

“I was the first guy to play catch with him in the backyard, in Swampscott, after he was well enough to do that, and he could barely see the ball well enough to catch it,” he said.

That was the starting point. Conigliaro missed the entire 1968 season, but had designs of making it back to the big leagues as a pitcher, since he’d pitched in high school.

But as 1969 approached, he began to see the ball well enough to hit it, and thoughts of a comeback became that much more realistic.

“Scar tissue had formed in the back of his eye, and his eyesight was 350-20. It was ridiculous,” said Petrocelli. “How could you see out of that?”

But slowly those numbers improved, until, several weeks later, it was back to 20-20, Petrocelli said.

“He came to spring training and started hitting the ball,” he said.

He made the team, and was in the lineup, in right field, on opening day. And in the 10th inning of opening day in Baltimore, he hit a two-run homer to give the Red Sox a 4-2 lead.

“What a story here!” exclaimed Red Sox broadcaster Ken Coleman as Conigliaro almost flew around the bases.

Among those greeting him when he got back to the dugout was Billy Conigliaro, in uniform for his first-ever Major League game.

“All I could think of was my parents,” he said, “and how thrilled they must have been.”

“I got chills when I saw that ball go out,” said Petrocelli.

Sal Conigliaro was working at Triangle Tool & Dye in Lynn while Richie was playing in a game for Swampscott High at Phillips Park.

“Someone had to come down and tell me,” Richie said.

Red Sox after that, hitting 36 home runs and knocking in 116 runs in 1970. But his eyesight started to deteriorate again, and he was traded to – of all teams – the Angels during the off-season.

“I was shocked. Stunned,” Petrocelli said. “What were they doing?”

But in mid-season, Conigliaro abruptly retired, saying his eyesight no longer made it possible for him to hit. He was hitting only .222 with four homers.

Aside from the irony of being traded to the team whose pitcher had nearly ended his life, the Red Sox got pitcher Ken Tatum in the exchange. Tatum had beaned Baltimore’s Paul Blair in 1970 and was never the same pitcher after that.

Nor was Hamilton. He never regained his form, and retired after the 1969 season.

Conigliaro attempted one final comeback in 1975, debuting at Fenway Park on the same day that Hank Aaron, newly-acquired from the Atlanta Braves, started as the designated hitter for the Brewers. But by mid-season he was hitting below .200 and Jim Rice and Fred Lynn were in the middle of historic rookie seasons.

Conigliaro became a broadcaster, first in Providence and later in San Francisco.

On Jan. 9, 1982, two days after his 37th birthday, he’d auditioned, apparently successfully, to take Ken Harrelson’s place as the Channel 38 color man for Red Sox broadcasts. His brother Billy was driving him back to Logan Airport, and they were near Suffolk Downs when Billy noticed Tony slumped over in the passenger seat.

He’d suffered a heart attack.

Billy took him right to Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. By then, however, Tony Conigliaro had lost too much oxygen. Even though he survived, he was never the same.

LeRoux, who had tended to him when he was hit, later purchased an interest in the team upon the death of owner Tom Yawkey.

And on June 6, 1983, while the Red Sox were about to have a benefit night for Conigliaro – with many of his 1967 teammates at the park to participate – LeRoux tried (and ultimately failed) to stage a palace revolt.

Conigliaro lingered for eight more years before he died in 1990 at age 45. Among the pallbearers were Petrocelli, Carey, Iarrobino and Tony Nicosia, another St. Mary’s friend.

“A day doesn’t go by that I don’t think of it,” said Richie Conigliaro. “But when all is said and done, I ask myself if I had a choice, would I take 37 great years, and all the living I could cram into them, or 70 or 80 lousy years? I know what my choice would be.”

(Overlines courtesy of “The Impossible Dream,” narrated by Ken Coleman.)