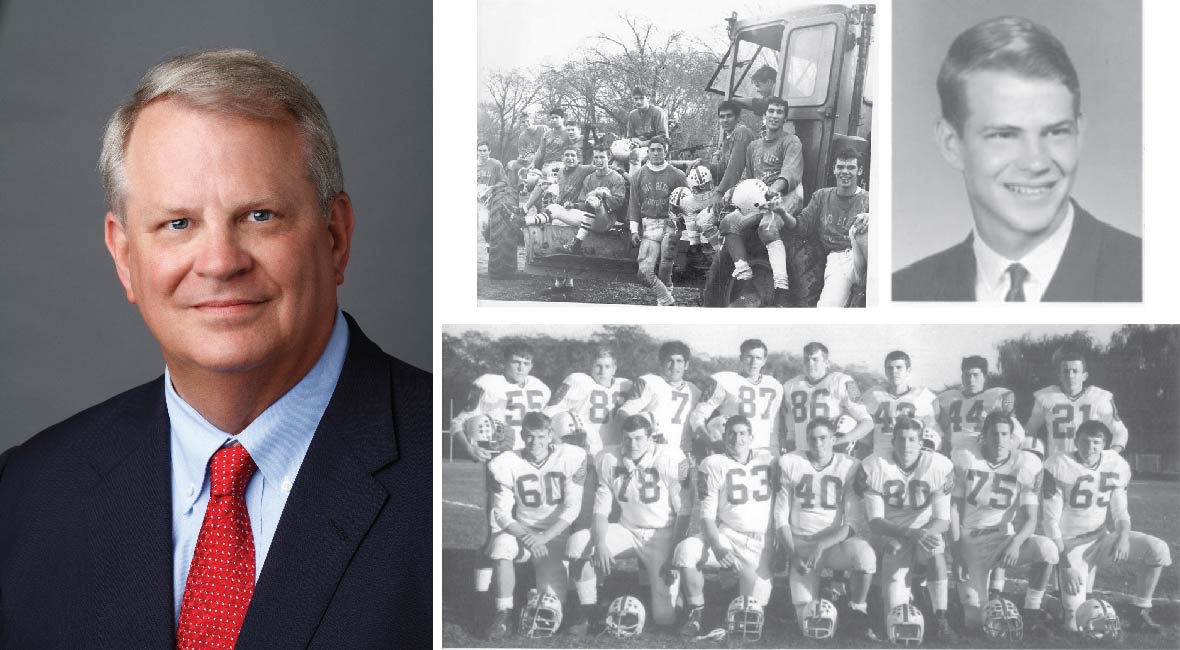

Carl Kester, a 1969 graduate of Swampscott High, is pictured (top left) with his Big Blue teammates; in his senior portrait; and on the football field (front row, far left).

By STEVE KRAUSE

The first thing you need to know about W. Carl Kester, George Fisher Baker Jr. professor of business administration at Harvard Business School, is that he is proof that lessons learned young stay with you forever.

Now, as a professor of corporate finance for both the Harvard MBA and the Executive Education programs, he takes those lessons and applies them to 21st century business practices.

“We learned a lot about the crisis of 2008 and 2009,” says Kester. “And one of the lessons is that you really have to walk the straight and narrow path; you don’t cut corners.

“As a corporate leader, it’s important to be transparent when you need to be, and are expected to be; and to be compliant with laws and regulations. That is terribly important. And effectively compliant organizations start at the top.”

He learned that as far back as high school, playing sports with an incredible array of teammates, Jauron chief among them.

“These were people who gave it the maximum effort at all times,” he said. “They did whatever it took not only to do it, but to do it the right way. There was no cutting corners with them.”

One of the aspects of management that Kester addresses in his MBA classes is corporate culture, and how people up and down the chain of command take their cues from the top.

“Where does the corporate culture come from? It comes from the top. The CEO, CFO, chief marketing officer, people like that. Be transparent. And be truly accountable for everything that happens in your organization.

“Is there some sentiment that while we have rules they don’t really count?” he asks. “Those are things that CEOs need to get right.”

Kester, who lives in Concord with his wife, Jane (they have three grown children, Kelsey, Eric and Kirsten), has a long association with the town and its football program. It goes back to when his father, Wally, and his uncle, Walter (the W. in his name stands for Walter as well, but he’s been called “Carl” since birth), both played for Hal Martin when the team was known as the “Sculpins” (Bondelevitch had the name changed to Big Blue).

And he said the football experience absolutely shaped him.

He graduated from Swampscott High in 1969, the same year as Jauron, and draws a lot of analogies between sports and life. For example, in an interview with the Harvard Gazette, the school’s official newspaper, Kester last winter expounded on why the New England Patriots’ Bill Belichick is such a good coach.

Boiled down, Kester said Belichick brings a clear vision (game plan) to every game; that while he may seem gruff and uncooperative with the media, “I have a sense he must be an extraordinarily effective communicator internally; communicates very well internally; that he can take his vision and communicate it well to everyone on the team (using the phrase “do your job” as an example); manages risks well; and doesn’t procrastinate when it comes to confronting issues.”

Compare that to what Kester says about the difference between a “boss” and a “leader.”

“Being a bully, that’s being a boss,” said Kester. “I always tell my students that it’s OK to be hard-nosed. There’s nothing wrong with that. But don’t be hard-hearted.”

And since this is essentially the story of a man who learned some of life’s most valuable lessons on the playing fields of Swampscott High, Kester uses the late Stan Bondelevitch, the architect of those great Swampscott High teams of the 1960s and ’70s, as an example of how to be hard-nosed without being hard-hearted.

“Stan could be tough as nails in some ways,” Kester said, “but you’d also see him off the field, and he knew how to approach you in a positive way to sort of help you out.”

Having always had an affinity for sports and athletes, it should come as no surprise that he is the past faculty chair of Harvard’s NFL Business Management and Entrepreneurial Program, an executive education program from 2005 to 2010 that offered guidance to NFL players who wanted to enter the business world after their football careers ended.

He said the concentration of entrepreneurship was a good one for NFL player because “for some players, it was a good career path.”

“These are competitive people,” he said. “Provided they handled their money well when they were playing, they had a good amount of capital to put down, and they had a personal brand name, which is a tangible asset, as we like to say.”

He acknowledges there are other career paths for former football players too. Some go into coaching, others into broadcasting, and some make a living as motivational speakers.

He acknowledges there are other career paths for former football players too. Some go into coaching, others into broadcasting, and some make a living as motivational speakers.

“But,” he said, “a significant number of former football players express an interest in business.”

He’s quick to say he didn’t start the program all by himself, nor was he the only one involved.

“I organized it and ran it, and recruited colleagues in entrepreneurial, management and negotiations, and other aspects of finance, to come in and take a general management curriculum for them so they could get a little bit of marketing, personnel management and negotiating skills, learn how to read a termsheet, things like that. Different people taught different things.”

The program began as a simultaneous initiative with the NFL’s league office and the NFL Players Association. They’d both been thinking of establishing such a program and approached business schools to help players who were interested in it.

The two-part program asked candidates to develop an idea. Then, after some instruction, the candidates would be asked to “figure out where they’d get the capital, who would be their partners, things like that.

“Then, they’d come back and have workshops,” Kester said. “It was within those workshops that they’d get some advice.

“Some were interested in real estate development, others interested in franchising, others were interested in restaurants and certain kinds of small businesses.

“We had workshops for everybody,” he said. “That’s where you’d get people to occasionally give them some advice.”

Of course, it was another ex-Swampscott football player who was instrumental and getting this off the ground: Alexander T. “Sandy” Tennant, another teammate of Kester’s.

“It actually started with Mike Haynes, who was on the Patriots in the 1970s … fantastic player, fantastic guy,” Kester said. “He’s a guy who actually went through the ups and downs of having an NFL career, and a good one, and then having some false starts in getting a post-career thing going.

“Sandy was the one who put Mike and me together,” Kester said, “and we came up with the program.”

When Haynes finally retired for good, and returned to the West Coast, Chris Henry, a director of NFL Player Development, took it over and still runs it—though no longer at Harvard.

“There were some players who liked this program who wondered why they did it at Harvard, figuring their alma mater can do it. They decided to move it around, at different schools. I don’t believe Harvard offers it anymore, to be honest.”

As much of an association as Kester has with Swampscott, he has an equally long one with Harvard. After getting his bachelor’s in economics from Amherst College, he got two master’s degrees—one from the London School of Economics focusing on international monetary policy, and the other an MBA from Harvard.

“Unlike most of my classmates, upon getting my MBA in economics I stayed at Harvard for the Ph.D. program.” He finished in 1981, immediately joined the faculty, and has been there ever since.

And as much as he’s been identified with sports all these years, Kester was also a National Merit semifinalist, a member of the National Honor Society, a state delegate and the senior class president during his days at Swampscott High. He stresses that academics is just as big a part of the puzzle as sports, even for elite athletes. And, once again, he uses Jauron as an example.

“Dick and I were classmates,” he said. “His name starts with J; mine with K. We were in the same homeroom all those years. I got to know him really well. He’s everything everyone’s ever said about him: a quiet leader, determined, and always putting in the extra effort.

“But another thing about him is that he was a darn good student. I think I was a pretty good student too. We both got to be in classes with some of the best students at Swampscott High. You saw him hit the books, study hard, engaged in class activity. He went to Yale. They might have wanted him for his athletic prowess, but he went to Yale because he was a smart guy.”

Photos: Courtesy of Carl Kester